Home | News | Books | Speeches | Places | Resources | Education | Timelines | Index | Search

Michael W. Kauffman

© Abraham Lincoln Online

MICHAEL W. KAUFFMAN, ASSASSINATION DETECTIVE

Part I: Looking Through Booth's Eyes

In 2002 we boarded a bus at the Surratt House Museum for a John Wilkes Booth Escape Route Tour, which traces Booth's journey after he shot Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. We traveled to Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., across southern Maryland, and into Virginia where Booth was killed. All day long the tour guide, Michael W. Kauffman, revealed new insights about Lincoln, Booth, the conspirators, and every imaginable connection to them. His commentary proved so compelling we thought you would enjoy a taste of it. We call him a detective because his methods resemble Sherlock Holmes, the fictional sleuth. The remarks here are from a September 2007 interview.Part I of our interview covers Kauffman's research for his book on Booth. In Part II: Walking in Booth's Shoes he relates dramatic personal experiences: rowing the Potomac River, jumping to the Ford's Theatre stage, and firing a tobacco barn. A short question-and-answer section completes Part II.

In 2004 Kauffman published a book on the assassination called American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. This account of Abraham Lincoln's murder and his killer reads like a fictional thriller, but rests on a stunning amount of original sources and research. Like Sherlock Holmes, Kauffman ably observes, collects, analyzes, and compiles his findings. We picture him nodding in agreement when Holmes says, "It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts," and "the gravest issues may depend upon the smallest things." Editor's Note: Since this interview, Kauffman published In the Footsteps of an Assassin in 2012, which details the route Booth took through Maryland and Virginia.

"For me the big question was always 'why?'"

Kauffman: I've been interested in the Civil War for as long as I can remember. My father was stationed at Quantico and we lived near Fredericksburg, Virginia, about the time of the Civil War Centennial. I was very young, and for me, history was all about going to the park. It was fun, and a chance to be with my family. There was no sense of having to memorize dates and troop positions and all that.I evolved from studying the Civil War to Lincoln. It's natural for most people to focus on personalities -- they are something anyone can understand. After the Kennedy assassination I realized what just happened had happened before. This led me into the Lincoln assassination. By the mid-sixties I was pretty well hooked on it and stayed with it.

For me the big question was always "why?" I read everything I could get on the subject, and it bothered me that so many writers were willing to settle for an explanation based on weak assumptions or unchecked information. One author, for example, claimed that Booth was avenging the execution of his friend John Yates Beall. As the story goes, Booth and Beall had been classmates at the University of Virginia, and when Beall was condemned to death for piracy on Lake Erie, Booth pleaded with President Lincoln to commute his sentence. Lincoln supposedly promised, then let the execution proceed anyway.

Of course, that's all nonsense. Booth never attended the University of Virginia, and there's no evidence that he personally knew Beall. A long line of celebrities pleaded for clemency, but none of the papers mentioned Booth. And more important, Booth doesn't seem to have mentioned Beall's case to any of his friends. The story is completely unsupportable, but that didn't stop people from publishing it as fact. And I'm sorry to say, that's typical.

Eventually I became convinced there was no way to explain what happened and why without looking through Booth's eyes, using his own words and actions. He knew his own motives, and unless he was controlled by some outward force, which is very doubtful, he would certainly have left some clues. In fact, he left them all over the place.

It was never very satisfying to read that this group or that was proslavery and therefore they had Lincoln killed. Like the Beall story, the connection with Booth had to be fabricated or assumed. That's why it makes sense to focus on the assassin himself, and let him tell the story. And he did try to explain the assassination. As we know, he shouted Sic Semper Tyrannus (thus always to tyrants) after the shooting, but many people have taken those words as the ravings of a lunatic.

Maybe, instead, they should have asked why Booth would think Lincoln was a tyrant. It seemed the only way to approach this was to get into Booth's personal background -- learn where he grew up and what people around him were saying, and hopefully figure out why they would say such things. It became an interesting exercise because I had a lot of problems with Booth from the very beginning.

"He didn't sound like a stereotypical lunatic"

On one hand, there were generations of people who said, "Well, he must have been insane." The insanity explanation wasn't satisfying because of how insanity is defined now and how it was defined then. It just didn't fit. Booth was so purposeful in how he built this conspiracy and what he did to set it up that he didn't sound like a stereotypical lunatic. So I wondered how I would explain a person to the public when I couldn't explain him to myself.Some sources referred to him a failed actor, an ardent Southerner, and even "half crazed." Yet when you return to his own time before the assassination you read what a great guy he was and how successful he was. Booth had strong political views, and apparently they weren't all that apparent until he shot the president. Otherwise it's hard to imagine why Julia Ward Howe and other Northerners would have felt such a deep affection for him.

The trick was to figure out whether his views were irrational, or just a natural product of his surroundings. I had to put myself in his shoes, finding out where he was from one day to the next, and what sort of political messages were being discussed in those places. It wasn't hard but it was tedious. He was a famous actor, so when he showed up in Columbus or Detroit or New Orleans, it was in the newspapers.

"I thought I would finish a book in a year or so"

There's a man named Art Loux who now lives in Kansas, and he and I and Constance Head were all going the same direction with this in the early eighties. But Art took his work a step farther. He followed the railroad line from Leavenworth, Kansas, to St. Joseph, Missouri, because that's where Booth went. He really went the extra mile, and eventually he published a thick book on Booth's activities almost every day of his career. That was a marvelous reference for me.Like most of the researchers I've known, Art is someone most Lincoln scholars don't know about. He doesn't seem too intent on changing that. He's retired and has much to look back upon and be proud of and I certainly thank him for his contributions. When you network with people like this you can build on their work. You have his pair of eyes, another person's pair of eyes, and can cover more a lot more ground. When I moved to this area in 1974, I fell in with a whole network of serious researchers, and very few of them have ever published. But I came here to do just that, and I thought I would finish a book in a year or so. My book actually came out exactly 30 years from the day I arrived in Washington.

There was much more to research than I ever imagined. If you go the National Archives and look at the Treasury Department records, for example, you'll see a list of their records, and it's not hard to imagine which of them might figure into this story. And then there's the State Department files and plenty of others. These records may not have been used before in an assassination study. Even the War Department records, with their Continental Commands, in April 1865 showed telegrams and messages passing from one Washington fort to another, or from a pursuit party looking for Booth, and messages sent back by courier. I don't know that anyone has ever used those, but they're very important.

Now I would say these sources are kind of a baseline; if you haven't seen them you really need to keep going. It may be a lot of extra work, but it's fascinating work, and the records help give a better sense of the times. They also fill in some blanks. For example, I wanted to write something about how General Grant heard of the assassination. I found plenty of newspaper and magazine articles written over the years, but they all contradicted one another. It's amazing how many people claimed they told Grant, all in different ways.

I was convinced long ago, at least for 25 years, that I would have to find a reliable way of resolving contradictions. The way it came about was embarrassing. At the time I was a television cameraman and saw someone shot and killed right in front of me. I was recording it and took the tape back to the station saying, "You're not going to believe what happened."

General Grant

© Abraham Lincoln Online

"I would have to find a better way of resolving contradictions"

The original records did not clear up the issue, but they did add some details. Grant was in Philadelphia when the news reached him, and he decided to take his wife across the river to New Jersey anyway. That was their home, by the way; they weren't just going there to visit their children. But the general came straight back to Washington from there, and to flesh out the details of that trip, I checked the Provost Marshal's files from the cities along the way. When Grant's train stopped at Wilmington, for example, he sent a telegram ahead ordering security arrangements through Maryland.It was very exciting to see messages like that, which hadn't appeared in an assassination book before. There are thousands of them in the Archives, and they show the tension and chaos of the time like nothing else can. Although those kinds of sources didn't resolve every issue, they helped a lot with my hour-by-hour approach. As for the identity of the man who broke the news to Grant, I simply gave up and used the most colorful character among the claimants. I also explained that his was only one of several stories out there.

I started spewing out my account of the crime scene. They put the tape in the VCR and my camera completely disagreed! I was puzzled because I wasn't making anything up. To this day, I know what I remembered and that's not what was on the videotape. I started looking for a way to explain it. I had worked in the FBI Academy in the seventies, and they had a number of courses on problems with eyewitness testimony. I attended and videotaped some of those sessions, but I didn't really think of it in terms of history.

My embarrassing incident changed that. I started reading about eyewitness testimony and found a number of books that lawyers use to try and pick apart people on the witness stand. It was fascinating. It's an entirely separate world from what the public gets now, especially in the age of 24-hour news. Now reporters try to grab something quickly, saying, "You saw what happened. What happened?" That's what goes on record, regardless of its merits. With historical events, the accounts dribble out over the course of many years, and writers give them all the same weight.

But eyewitness experts, relying on brain studies and experimentation, have proved that memory is only accurate for a short period of time, and they're easily contaminated by other accounts. So, to counter that effect, I had to depend on the earliest accounts I could find.

There was just one problem. In 1865 people did not write down the small things, such as the color of the wallpaper, or the things that were too obvious to mention at the time. I had to get that information from later sources. It didn't always feel right, but often it was the only way to flesh out the story. As a compromise, I developed a sliding scale of importance. Trivia didn't matter so much, but if I were accusing somebody, or relying on information as "evidence" of great historical value, it had to go through all kinds of tests.

That worked fairly well. The memory studies were a touchstone to my whole approach. It was important not only to get the earliest sources available, but to determine their quality as well. People usually exaggerated when they told the story years after the fact. But right from the beginning, some people put themselves in the middle of things, making themselves more heroic or more deserving of reward money. Maybe they're looking for money or attention, or maybe think that helping the government is just something that every good citizen does. So I had to think about the circumstances behind every statement, and the background of the person making the statement. I couldn't do that without researching those people, and that in itself was an eye-opening experience.

"I knew nothing about databases or computers"

I took the records from the National Archives -- the prosecution's records, the original conspiracy trial testimony -- and using only that, put it into a database. I knew nothing about databases or computers. The salesman who sold me my first computer said, "If you live to be 100, you will never use all 20 megabytes on this hard drive." In hindsight I'm thankful I started out that stupid.I worked from microfilm, which I bought when it was still affordable. It was only $3 a reel then and it's something like $68 now. I started this when I was in my early teens. I even collected cdv's and related things when ordinary folks could afford them.

At the time I was frustrated with my data collection process because it was so unprofessional. Even now a database administrator would look at what I've done and roll his eyes, thinking of all the wasted time. But that extra effort, that extra typing, is what paid off. I messed up so many times, and each time I had to start over. If I had only typed those records once I might have missed a lot. But every time I had to start over, I came at it with a different perspective. On the second or third pass I would know that I had seen this issue a few times before, but had failed to make note of it the first time around. So my perception evolved over time, and some small very things eventually become more important.

The database was centered around events. I set up a separate field for the location of the source document -- reel and frame, for example. Then another field would give the time of the event it described. Another one told who provided the information, and another gave the location of the event. I set up another field for the date that this supposedly happened, and a separate one for the date this was reported. Finally, I added an index for the whole file. From all that, I could have the computer make a chronological readout of the investigation simply by listing every event, sorted by the date of the reports. This allowed me to figure out what people knew at a certain time and what was still in the future. That turned out to be the outline of my book.

It was very important to keep everything in context and not look ahead, to achieve a sense of immediacy. There have been so many conspiracy theories which asked, "Why didn't they do that?" The answer is usually that people in 1865 couldn't see that broadly, and they certainly couldn't look ahead. They couldn't anticipate things we take for granted now, such as sealing off the roads from Washington instantly when Booth fled from the murder scene. They not only lacked effective communications, but they were confused and in shock. This comes through very clearly in the chronology.

By April of 1865 Stanton had heard more than his share of wild rumors -- outlandish stories, some of which were deliberately planted to cause panic -- so he assumed this was another one of those. But before he left his house, along came Major Norton Chipman, a War Department attorney, with news that Secretary of State William Seward had been attacked. Stanton, weighing the two, must have thought, "Here's a near-stranger telling me that Lincoln's been shot, and here's the explanation -- it's really Seward instead. Major Chipman had actually been to Seward's house, and had seen the carnage with his own eyes.

Edwin Stanton

Library of Congress

"That was the moment when he knew this was a conspiracy"

Take the case of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, for example. I tried to piece together a chronology of how he learned about the assassination and what he did in response. This is important because people have blamed him for lapses and delays in the pursuit of Booth. For one thing, he didn't even go straight to Ford's Theatre when he heard the news. Though the database didn't solve that mystery, other primary sources did.Two men were passing in front of Ford's Theatre when they saw people pouring out of the place shouting, "The president's been shot." One of those men was from Steubenville, Ohio, and he knew Stanton's son. So the Secretary was on his mind, and he thought someone should break the news to him. The two ran eight blocks to Stanton's house, which has to take time. The Secretary had already gone to bed by the time they arrived, and it took more time for him to get dressed.

It's only when he gets there that he finds out that both men have been attacked. That was the moment when he knew this was a conspiracy. Imagine the emotions he must have been going through. Two heads of government have been attacked -- maybe more -- and he could be targeted as well. Are Confederate raiders going to come charging into the city? The sense of terror must have been overwhelming.

You can read a little of that in Gideon Welles' diary. Welles saw Stanton at the Seward house, and when they learned of the shooting in Ford's, he insisted they go there. He figuratively gave Stanton a shove out the door. That mental paralysis, on Stanton's part, was perfectly natural, under the circumstances, and it wore away pretty quickly.

President Lincoln had been carried to the Petersen House, across from the theatre, and when Stanton arrived there he took control of the situation. But it took time. His initial stumbling is evident in the first messages he sent from there. It's as if Stanton thought, "Do I really want to say who the murderer is when I'm not 100% certain?" People came to him saying it was someone who looked like Booth, but this was an enormous crime, and most people were hesitant to accuse him point-blank. They were sure about it later, but not during those first hours, and Stanton also had some trepidation.

It's clear that Stanton pulled things together, but it took time -- maybe a couple of hours. His first message had a few false starts, with lots of words crossed out. Apparently he was unsure of how to say things and didn't know how much time he could put into the effort. But a courier ran his message over to the War Department, and the telegraph operators cleaned it up. They turned it into a work of literary art.

Stanton, inadvertently, also may have created the inverted pyramid style of journalism. It looked as if he figured initially, "I'm just going to dash off a quick sentence or two, maybe a paragraph, to tell what happened." So he put the important information in that paragraph and then added something of slightly less importance. As he kept on going the information became progessively less vital. That style of reporting became standard practice in the news business, and remained so for many years.

"In some ways it's already stranger than fiction"

When you try and get into the head of someone, you can see things in a whole new light. By focusing specifically on Stanton's behavior, then on Booth's, and so on, I realized how much the human element drove the story. Novelists do this sort of thing all the time, but writers of non-fiction are usually too busy looking beyond the characters.The story of the plot and assassination has got absolutely everything -- people, power, intrigue, and deception. So it's a bit annoying when writers change things around to make it more exciting. It doesn't need that. In some ways it's already stranger than fiction. It's got such a great cast of characters. There's Boston Corbett [Booth's killer], Detective Lafayette Baker, and an enormous number of others. Booth and his high-society friends were all fascinating, and of course Abraham Lincoln and his own circle represented the pinnacle of power at the time. The conspirators and the detectives all manipulated one another, and all had something to gain or lose. With all that, why tinker with the truth?

I was concerned I might not do the story justice. I had spent decades studying perception and memory, so I had a good idea how to sift through the evidence. But I was not so confident in my writing. I got some good advice, though. Simply stated: History is about people, the interactions of people. Take on the role of one person at a time and follow up the story from beginning to end, then repeat as necessary for each character.

It was necessary to consider each relationship at each step in the story. For example, when John Wilkes Booth met Sam Arnold in 1864, I imagined what was going through his mind. What did he think about Arnold? What did he know about him? Did he trust him? Fear him? How could he get Arnold to do something for him? Unconsciously, Booth would probably ask those questions again with every change in circumstances. Knowing that, I keyed on everything that might have affected those relationships and re-examined the story with every new development.

That changed everything; it absolutely changed the whole story. Now it isn't enough to say that Booth and Arnold trusted one another. I have to be specific about the date. They may have trusted one another on March 14, but by March 16 they had gone through a falling-out, and made each other extremely nervous. That distinction is crucial in figuring out their behavior from one day to the next.

"It was possible to see how the plot worked"

So let's stay with Booth and Arnold for a minute. We know that they knew each other, but it's important to figure out what they knew about each other in 1864. By then they had not seen one other in 11 years. They had changed remarkably in the meantime, and when they got together that summer, they would naturally discuss the intervening years. The war was still in progress, and it wouldn't take long to get a good sense of where their sympathies came together. From then on, we have to keep revising the relationship. So I asked my database to give me everything Arnold did with Booth in chronological order, then give me everything Arnold did with this other person, and this other one. And so on. If Arnold began hanging out with people Booth didn't trust, it affected the trust between them as well. By examining all of these individual threads it was possible to see how the plot worked.In this way I could find out what Booth knew at any given time, and I could also get a good sense of how often he lied about what he knew. In late 1864 he was already deceiving people about his connections and his whereabouts. Later it became clear that he was also lying about his intentions -- lying, that is, to his own people. He's building a conspiracy for his own reasons, and by early 1865 the political situation had changed and those reasons no longer made sense.

It's not hard to figure out why Booth lied. He wasn't just hiding his plot from the authorities. He was also tailoring his recruiting pitch to give himself legitimacy in the eyes of his cohorts. This selective withholding, releasing, and misdirecting of information had a definite purpose, and sometimes it compromised the safety of people who posed a threat to Booth's plot. Booth himself called it "sacrifice," and since it was directed at people he could not trust, it had the most devastating effect on those who least deserved it. It was all very cold-blooded.

Somewhere along the line, his plan to "capture" the president had lost its charm for him, but he could hardly just let go of the men with whom he had conspired. They knew too much. So he pretended to keep their scheme alive, while making no effort to carry it out.

Sam Arnold eventually called him on it, and pointed out that there was no longer any reason to pursue the conspiracy. Booth had always claimed that his goal was to capture the president, and holding him as a hostage, force his administration to exchange POWs. But as Arnold pointed out in March, the government had already resumed the exchange on its own volition. So why were they still together, plotting in secret? What were they supposed to accomplish? Suddenly it became clear that this wasn't a capture plot at all, and at that moment all the relationships changed. Some of the conspirators were scared to death, and they ran for their lives to get away from Booth. Within hours, others moved up in the pecking order. Frankly, they were too stupid to go away.

The actor Sam Chester didn't want any part of Booth's plot, but he also didn't want to come forward and say, "This guy is dangerous." John Mathews was a rookie in the business, and he was even more intimidated. When Booth told him about the plot, Mathews reeled back, saying, "I can't have anything to do with that." From then on, you can see Booth building a strong evidentiary case against Mathews to make it look as if really he was involved. He did the same thing to Chester and any number of people. Some of those people had joined the plot, some knew nothing about it. All they had in common was that Booth didn't trust them.

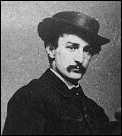

John Wilkes Booth

Library of Congress

"You're not trying people for what they did but for what Booth did to them"

I never quite figured out Booth's original intention because he kept it to himself. But given his lifelong interest in so-called "martyrs to liberty" -- what his classical education taught him, what his father had left to him, the historical outlook he had -- these sources all spoke about killing. Nobody ever wrote about kidnapping Caesar. So his mindset was really about ridding the country of a tyrant, not just using him as a bargaining chip. But meanwhile, he's pushing a completely different plan, and it doesn't make sense. Even some of the conspirators thought it was bizarre. At their trial, they tried to argue, "No, no, what we did was entirely separate from the killing." That was an honest claim for some of them. But Booth was a very persuasive person, and he had them believing, for a time, that they could pull off the capture of the president. Even if they were skeptical, people were afraid to cross him, especially actors. He was very powerful in their profession.

Amazingly, this wasn't clear until I was almost finished with the book. I got to the trial of the conspirators and expected to say, "Eight people were put on trial and four were hanged," and leave it at that. But in reviewing the transcripts again I noticed a statement by one of the defense attorneys. In essence, he said, "You're not trying these people for what they did, but for what Booth did to them."

"It seemed to explain the different things Booth wanted people to believe"

After that, I reread the whole trial transcript and saw the case in an entirely different light. For the first time, I realized how much of the story was affected by the rules of evidence. I also realized that, from the attorneys' point of view, the entire trial was dominated by a single issue: whether the defendants should be allowed to give their own side of the story. Criminal courts -- both civilian and military -- did not allow a defendant to testify on his own behalf. But as the prosecution laid out its case, the accused began to realize how much Booth had depended on that rule. He had created false impressions that only they could refute. He had joined them in harmless conversations that now seemed sinister in light of later events. The government had more than enough witnesses to tell about those events. And as everyone knew, the defense was powerless to explain them away.It's not like they didn't try, but the prosecution stomped them down at every turn. They had a huge advantage, and weren't about to give it up. So, reading their arguments, it occurred to me that "defendant declarations" was a life-or-death issue for the prisoners. That was like a light bulb coming on. All the lies and manipulation suddenly made sense. If Booth could create an air of intimacy with someone, he stood a good chance of keeping them quiet. Suspects can't be witnesses.

It's important to note that this rule wasn't an obscure technicality. In 1865 everybody knew that the words of a defendant could only be introduced by the government. If it were any other way, a criminal might build a whole nest of lies simply by passing them along to unsuspecting, honest people. But suspects didn't fall into that category. Their words were automatically viewed with skepticism -- unless, of course, they were useful to the prosecution.

Nowadays it's called a "statement against interest." A suspect's words have a lot more force if they tend to prove his guilt. He obviously wouldn't make that kind of thing up. If he had told someone, "I'm going to New York," and was accused of killing someone in Manhattan that night, a prosecutor could bring in that witness to suggest that the defendant was at or near the scene of the crime. On the other hand, if the murder had taken place in Richmond, the defendant would not be allowed to introduce the same witness to say, "No, he was in New York -- he told me so."

That's how it worked, and it seemed to explain why Booth spread so much disinformation about himself and the people he didn't trust. He practically handed those people to the authorities, but people like Powell and Herold -- he never mentioned them.

Louis Weichmann, who boarded with Mrs. Surratt, starting nosing around asking a lot of questions, I don't think he ever learned the truth, and I don't think he was part of the plot. Still, the evidence against him was overwhelming. There was a simple reason for that: Booth didn't trust him, nor did John or Mary Surratt. Apparently he was considered a serious threat, so when Booth or John Surratt went somewhere they would drag Weichmann along. Then they would take him aside for a few words. What they said was perfectly innocuous, but there were all these witnesses in the room saying, "Oh, the three of them went off to themselves in the corner."

That put Weichmann in a very difficult position. He tried to say, "No, no, that's not the way it was," but the pressure was immense. He had no idea, but the prosecution knew he was telling the truth. On the night of the assassination Colonel Timothy Ingraham, Provost Marshal of the Defenses North of the Potomac, sent a team of men to search Booth's room at the National Hotel. They went through his trunk and took what seemed to be relevant, leaving the rest. One of the items they took was a letter written to Weichmann by his priest and confidant. The letter, which referred to Weichmann's confusion about what was going on, had been intercepted and turned over to Booth.

For a long time I looked for the lieutenant who led the room search. I knew he was from Philadelphia, but that was about it. Back in the eighties I was giving a talk there, and Mike Cavanaugh was driving me around. He asked if I knew about the G.A.R. Museum, and said that they had the handcuffs that were found in Booth's hotel room. I already knew that Lt. William H. Tyrrell had asked Stanton if he could keep them as a souvenir, and Stanton agreed. So I was thrilled to see the name Tyrrell connected to those cuffs at the museum. I don't know what happened to Booth's trunk. Like so many things, such as Lewis Powell's bloodstained clothing, they have "walked away" over the years. Maybe they'll turn up someday.

Click here for Part II: Walking in Booth's Shoes

Related Information

Assassination Links

Assassination Books

Lincoln Assassination Expert Scours Iowa for Clues

Home | News | Education | Timelines | Places | Resources | Books | Speeches | Index | Search Copyright © 2007 - 2020 Abraham Lincoln Online. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy